Interdisciplinary research: Part Two - My Robotic Research Assistant

This post is part of a series on the topic of interdisciplinary research. Each member of the current blogging team is involved in some form of interdisciplinary research, and we’ll be sharing our individual experiences of this every Wednesday from the beginning of March to the beginning of April – so stay tuned!

As a postgraduate research student, you often find yourself answering either one of the following two questions: “So, when do you finish?” and “What is it you are studying?” (often the former question is asked before the latter). Doing a research degree means having to perfect your elevator pitch for those moments, when you are mentally counting down from 10 to keep calm about the fact that you have ALL the things to do and merely one and a half years left to do them in.

Nowadays, my pitch goes something like this: I am interested in how people perceive and interact with robots. I am not a computer scientist, I am not working with AI and no, I am really not worried about our robotic overlords taking over (any time soon). After clearing up any potential misunderstandings, I often end up having a very interesting conversation with an equal parts suspicious and intrigued Glaswegian cab driver.

I find this confusion very understandable – why would an experimental psychologist investigate robots, of all things? My fellow blogger Ann noted in her post last week that conducting interdisciplinary research is a privilege, but also comes with its own challenges.

So, why is it that I employ a robotic research assistant in my experiments? There are at least two good reasons for doing this:

Imagine setting up an experiment that investigates social interaction. You want to know more about the underlying processes in the brains of two people interacting with one another. In the past, many social neuroscience studies have presented their participants with images or videos of social interactions. The reason for doing so is that researchers want to keep a high degree of experimental control over their stimuli, so that all participants observe exactly the same experimental conditions. But how do we know that observing a social interaction leads to the same response in the brain as a real, embodied interaction would?

This is where “ecological validity” comes into play. Put differently, researchers are also concerned about whether their experiments capture a real-world phenomenon, and if their results will translate into an everyday context. Experimental control tends to clash with our desire to design ecologically valid experiments. Typically, you have to compromise one for the other.

However, using robots offers a way out of this dilemma: here comes the research assistant that will repeat its behaviour again and again and again, without ever getting tired (unless of course its motors are running hot). In other words, you can now design experiments that are ecologically valid and at the same time ensure high experimental control.

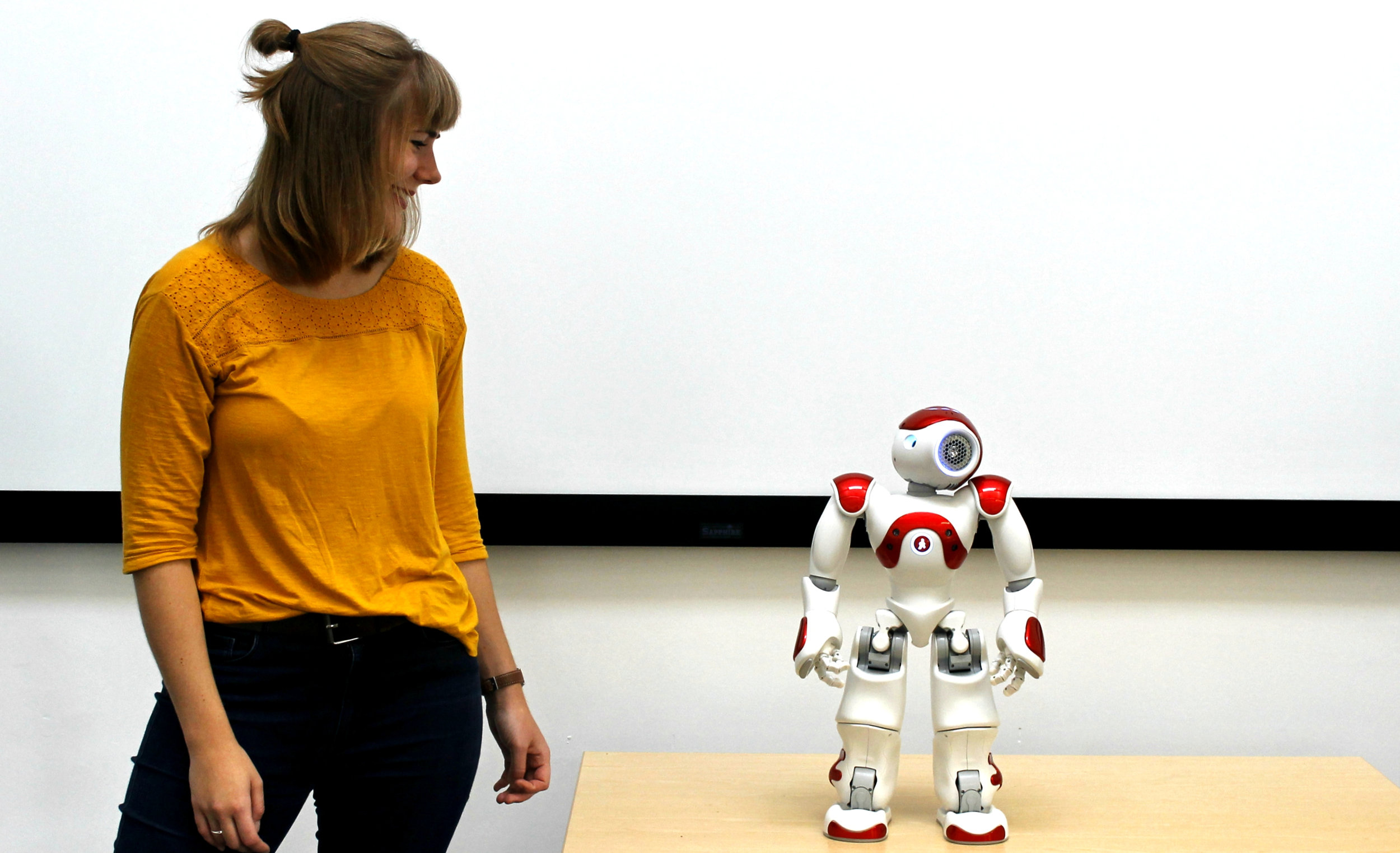

One of my mechanical friends.

Another benefit to using robotic research assistants is that they allow us to answer questions on how flexible our “social brain” really is. In recent years, we have seen robots move out of the factories and inside the homes of people. Whether this is in the form of an ALEXA system, a humanoid robot giving you directions at the airport or a little robotic toy that looks a lot like Disney’s Wall-E, social robots are on the rise.

People all over the world are excited by the idea that robots could alleviate loneliness, motivate us to exercise and keep us company when we are recovering from illness. But in order for robots to fulfil their potential, they first need to work a little bit on their social skills. This is where the expertise of social neuroscientists and psychologists can help.

Based on what we know about human-human interaction, we can find out which things work for human-robot interaction, and which things don’t. Now, while all of this is exciting, there are some challenges attached to working in a field that uses very different research methods, publishes in different journals and sometimes seems to speak a another language altogether.

I remember when I first started collaborating with the programmer in our lab. She always talked about “users”. I was confused about this for an embarrassing amount of time, until we figured out that we were both talking about the participants. I had to learn a new vocabulary, that involved “wizards”, users and robots, and had to be mindful of the scientific context I was in.

Another thing to keep in mind is that different fields of research publish in diverging journals and have widely varying standards for publication. For example, researchers in human-robot interaction tend to publish short papers in the proceedings of conferences, whereas psychologists would publish long(er) research reports in journals, each one following a very specific set of publication guidelines. All of these methodological differences require you, the interdisciplinary researcher, to adopt a flexible approach and keep an open mind to another field’s customs and practices. It also helps to read publications from both fields, so you are prepared when it comes to deciding where and how you want to publish your findings.

In the end, I am convinced that the advantages of working in an interdisciplinary field of research by far outweigh the occasional struggles. In fact, we know that diverse teams reach better conclusions, and we need to broaden our horizon if we want to address scientific questions creatively. And obviously, working with robots is pretty cool too.

Find out more about my research on my lab’s website or via our project pages.

Photos by Elena Giacomazzi