How to Give a Winning Research Presentation

With the annual progress review season starting, I thought I’d run over some pointers for a good research presentation. Mine was last week, and it won me an award, so I hope to be able to give you some winning tips! I’m sure you have some tricks of your own, too: let us know in the comments or over on Twitter (@UofG_PGRBlog).

Preparation

We find lots of reasons to moan about the annual progress review (APR), but it is simply an exercise that can help you if you take it seriously. Writing the report forces you to update your understanding of the literature, summarise your findings into paper-ready figures, and plan ahead for next year. The latter in particular can really help you focus on what steps are most important to progress your research – whether a review panel reads it or not is less important. Equally, if your institute organises APR presentations, try to see them as a training opportunity before a conference presentation, your viva, or future job interview. If your APR does not include presentations, I hope these tips will be useful for other opportunities you’ll have to present your research!

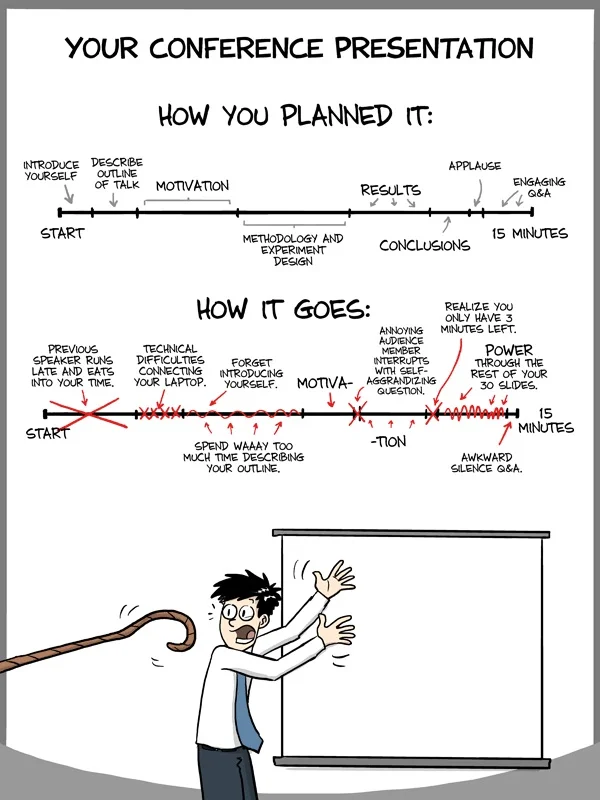

Conferencepresentation

Image credit: “Piled Higher and Deeper” by Jorge Cham,http://www.phdcomics.com

As always, preparation is key. In past years, my presentation was always a stressful last-minute rush job, as I would spend too much time conducting some final experiments I really wanted to include. But in fact, the annual review is just a showcase of what you’ve done so far, and you are not expected to have a finished story yet. So, this year, I managed my time better to ensure I was better prepared, using the following steps:

Define your audience

As a PGR, you’re a specialist in a defined research field. It is likely that other people, even in your own institute, are not familiar with the required background needed to understand your topic, the research methodology you are using, or the specific details that are considered general knowledge among your peers. When you present to your own research group, the level of introduction and explanation will be different from a presentation for the whole institute. This means you have to simplify your work to make it more accessible, but this does not mean you are dumbing it down: it shows that you know how to communicate effectively. Capture your data in clear, understandable figures and graphs, and summarise what they mean in written and spoken word. This will help guide your audience along as your story progresses.

What message do you want to convey?

You’ve spent anywhere from one to three years on your research, so it will be impossible to include all you have done in a 20-minute presentation. Think about what conclusion you want people to walk away with, and include only those key results that allow you to tell that narrative. It is always tempting to include as many spectacular results as possible, but if they take time away from a decent introduction to your topic or the methodologies you used, many people will not actually be able to interpret those results or understand the implications of your research. Less is often more!

Balance results and methodology

It is likely that many of the methodologies you use are highly complex, technically or conceptually. Because we spend so much time optimising them, and possibly developing methods ourselves, we often get carried away with methodological details. Your presentation should primarily focus on what you are doing, your results and conclusions, rather than how you are doing it. Only explain the methodology in detail if it is really crucial, you can always just state that “you have optimised a methodology to measure x” if it would too time consuming to explain all experimental details. Equally, at the end of your presentation, when you want to discuss your future plans, do not bore your audience with the methodological details of what you plan to do. Rather, focus on the big questions you want to answer and how these contribute to your end goals.

Explain your figures

Much of our data is summarised in complex figures. You may be used to looking at them and can interpret them quickly, but it may not be as easy for someone who sees them for the first time. Indicate what the axes represent, explain the scale used, the different data sets that are displayed, and the colour coding. Then explain what the data show, what you can conclude from it, and what this result means for the research question you’re trying to answer by connecting it with your previous results. Then, use a connecting sentence to relate this result to the next piece of research you will show.

Grouppresentation

Image credit: “Piled Higher and Deeper” by Jorge Cham,http://www.phdcomics.com

Tell a story

A research presentation is not just an introduction, a string of results, and the conclusions at the end. We are used to this format for research papers, but a written paper allows people to go back and forth between the different sections if they missed a detail. In contrast, a presentation needs to be clear from start to end: if your audience gets lost along the way, it will be difficult for them to find their way back. This may mean that you give a piece of introduction, show your first results and connect them, draw conclusions, and introduce your next question based on previous results. Then, you may have to introduce a new model or methodology you used, leading to some more data and results. I’d encourage you to summarise your presentation at the end, but this does not mean that all conclusions should be drawn only after your summary: use concluding slides and sentences throughout to build your story.

Design and visuals

As scientists, we value hard data and often think they should speak for themselves. But data are just numbers – it is up to us to display our data in a way that is most easy for our audience to follow. Title your slides with the conclusion of what you are showing on that slide and only include other text when absolutely necessary. Be brief and concise: avoid writing entire sentences on your slides and never just stand there and read them out, rather make sure that the text and spoken word are complementary. Ensure your letter size is large enough for people in the back row to read and test this in advance so you can adjust it if necessary. If you include photos, movies, or time lapses: test if they work. If you have to switch from Mac to Windows or vice versa, text, symbols, and figures often disappear or get moved around, so always make sure to check.

It is also important to be consistent in your colour schemes: if you compare two datasets throughout, make sure all your figures use the same colour for each set. When you suddenly flip it around in a new figure, people may not notice and interpret your results in the opposite way. The same goes for introductory slides: it is tempting to take figures from review papers and just include those, but they will all have a different style, colour scheme, and may include unnecessary details that are confusing rather than complementary to your story. It takes a lot of time to make these figures for yourself, but it will add a lot of consistency to your talk if you use the same style for your introductory, concluding, and summarising figures (make sure to add a clear citation or mention “figure adapted from x” if there is substantial overlap, or you are showing someone elses findings that are not considered general knowledge). Equally, use the same lettering throughout. We’ve all seen senior group leaders present a collection of slides that they obviously just combined from the work of several students and postdocs, which just ends up looking really messy and confusing. Finally, when choosing colour schemes, be mindful of people with colour blindness, who have trouble discriminating green and red. When using heatmaps or rainbow-colored images it’s best to go for safer combinations such as green-magenta, red-cyan, or yellow-blue.

Execution

Practice, practice, practice. The more relaxed and clear you talk through your presentation, the easier it will be to follow for your audience. Write out what you want to say and memorise it over the span of several days, practice your presentation, and time yourself to ensure you stay within limits. If you worry about speaking too fast, record yourself with your phone and play it back to decide if you need to adjust. Ask your colleagues for a practice talk to get some feedback – no matter how well you prepare, it is always helpful to receive some feedback on the content, structure, visuals, and pacing of your talk.

If you know you get jittery during a talk, ensure you get a good night’s sleep and go easy on the caffeine. If you’re nervous and get a dry mouth, chew some gum before your presentation and bring a bottle of water so you can take a sip during your talk – this also introduces a natural break to quickly gather your thoughts if you become a little lost.

Finally, no matter how stressed you are, try to convey as much enthusiasm as possible. Smile! Try to be funny! If it doesn’t fit your personality, of course you do not need to turn your presentation into a comedy show, but if you speak in a monotone fashion without displaying any passion for your work, it is unlikely that your audience will become enthusiastic either.

Questions

Image credit: “Piled Higher and Deeper” by Jorge Cham,http://www.phdcomics.com

Question time

Many of us fear the Q&A after a talk. What if they ask the exact thing you don’t actually know? But there’s really no need to worry: nobody expects you to know everything. Don’t try to talk about something completely unrelated just to look like you have a good answer – I always feel the most distinguished speakers are able to say “Hey, that’s an interesting suggestion and we haven’t looked into that before, but it’s worth exploring - thanks”. Equally, if we do know the answer to a question, we often want to show that we do. Many people don’t let the questioner finish their sentence but jump right in with their answer (I definitely have that tendency – it also doesn’t help that many academic questions seem to be endless monologues to just show off) but just reign yourself in, wait until they finish, smile, nod, and start your answer. Be concise, too: no answer should take several minutes! It helps to prepare questions that you think you will get before your talk, so you have to-the-point answers ready to go in your mind.

Finally, one element I find hugely important is the acknowledgements section. Due to time limitations many people brush over this, but this is your one opportunity to show some public appreciation to your supervisors, colleagues, and collaborators. Though independence is celebrated in academia, it is unlikely you did your work all alone and acknowledging the contribution of others is the kind and right thing to do. Good luck!