New Initiatives Funding: The Mystery of Edwin Drood and Public Engagement

In a previous blog post Louise Creechan, PhD researcher in English Literature, wrote of her experiences working on The Mystery of Edwin Drood: a musical adaptation of Charles Dickens' novel which was funded by the University of Glasgow's New Initiatives Funding. Here she explains how the researchers on the project harnessed the musical’s potential to engage audiences in the lesser-known Dickens novel and its associated mystery:

In collaboration with a local musical theatre company, Mad Props Theatre, we staged a musical adaptation of Dicken's unfinished novel: Rupert Holmes’s The Mystery of Edwin Drood. What is particularly unusual about this musical is that the ending is decided entirely by audience vote which, in our opinion, makes it the perfect medium for active public engagement.

In the lead up to the production, our mathematician worked out the total number of possible endings for the show (an enormous 358!) which aided the production’s marketing campaign - many of the comments received on the theatre company’s Facebook page were confused as to how a single production could offer so many alternatives. We responded by posting this blog post which illustrated how we calculated the possibilities and which ending, based on the figures from the 2012 Broadway revival, was the most likely.

The way the audience vote worked in performance was as follows:

First the cast were asked to vote on whether or not Edwin Drood is alive or dead. They always answer that Drood is dead to cue a ‘diva rant’ from the actor playing Drood who subsequently is eliminated from the detective vote.

The audience is then asked to vote on the identity of the detective Dick Datchery from the following candidates: Rosa Bud, Neville Landless, Helena Landless, Rev. Crisparkle, and Bazzard. This vote is taken by audience applause and is most commonly Bazzard, as the character bemoans his small role throughout the show.

Then the audience is asked to vote on the identity of the murderer from the remaining candidates with the addition of Durdles, the Princess Puffer and John Jasper; they are discouraged from voting for the clear villain of the piece, John Jasper, as it seems too obvious for Dickens. This vote is a secret ballot taken by cast members in the audience.

The detective accuses John Jasper who always confesses before Durdles reveals the true murderer.

After the murderer’s confession, the audience are asked to ensure a happy ending and to vote by applause for the two characters who are to be lovers. This is usually a source of comic relief as inappropriate options can be paired, such as the ingénue with the drunken, unwashed stonemason and the Landless twins with one another, much to their disgust.

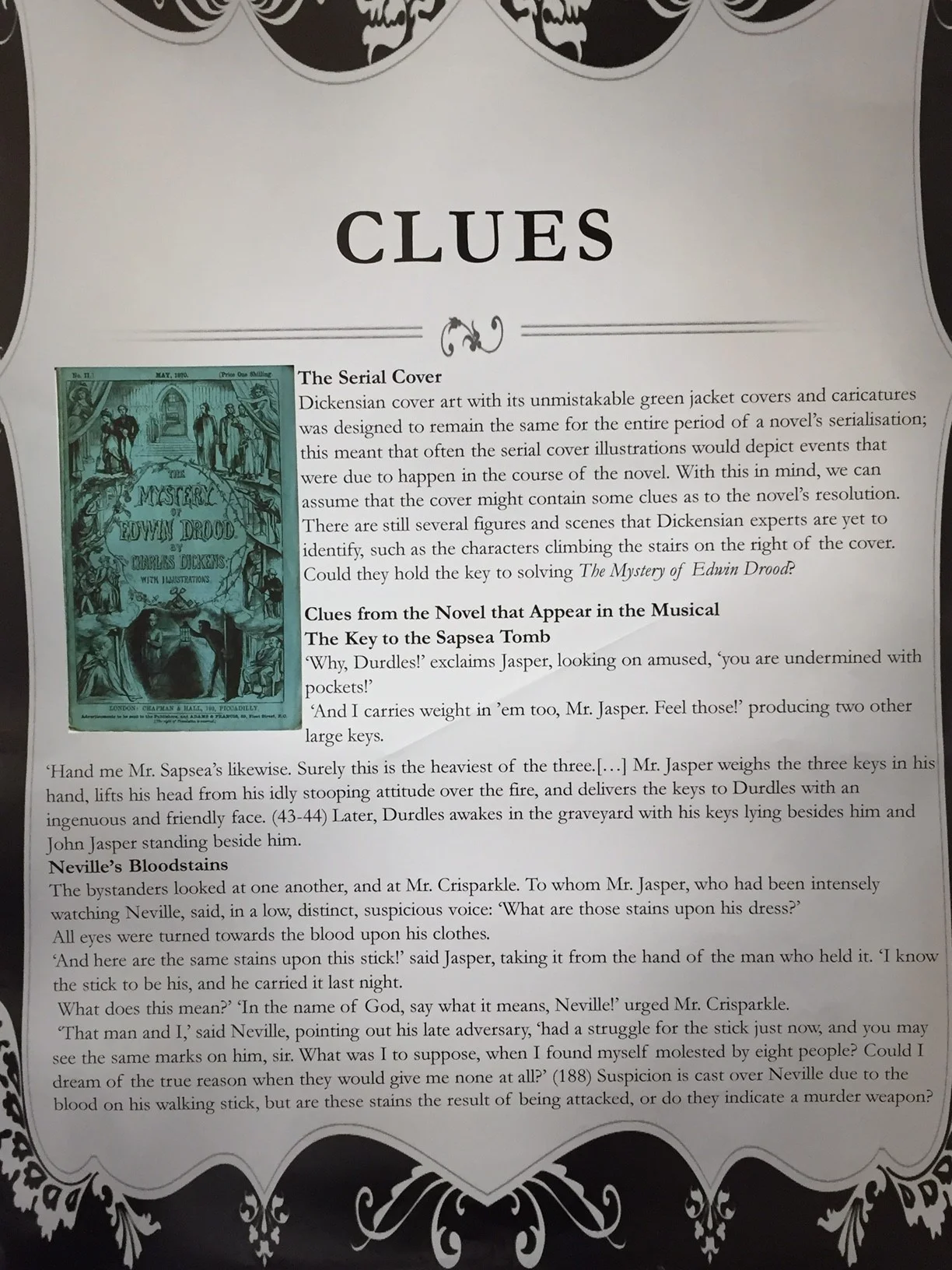

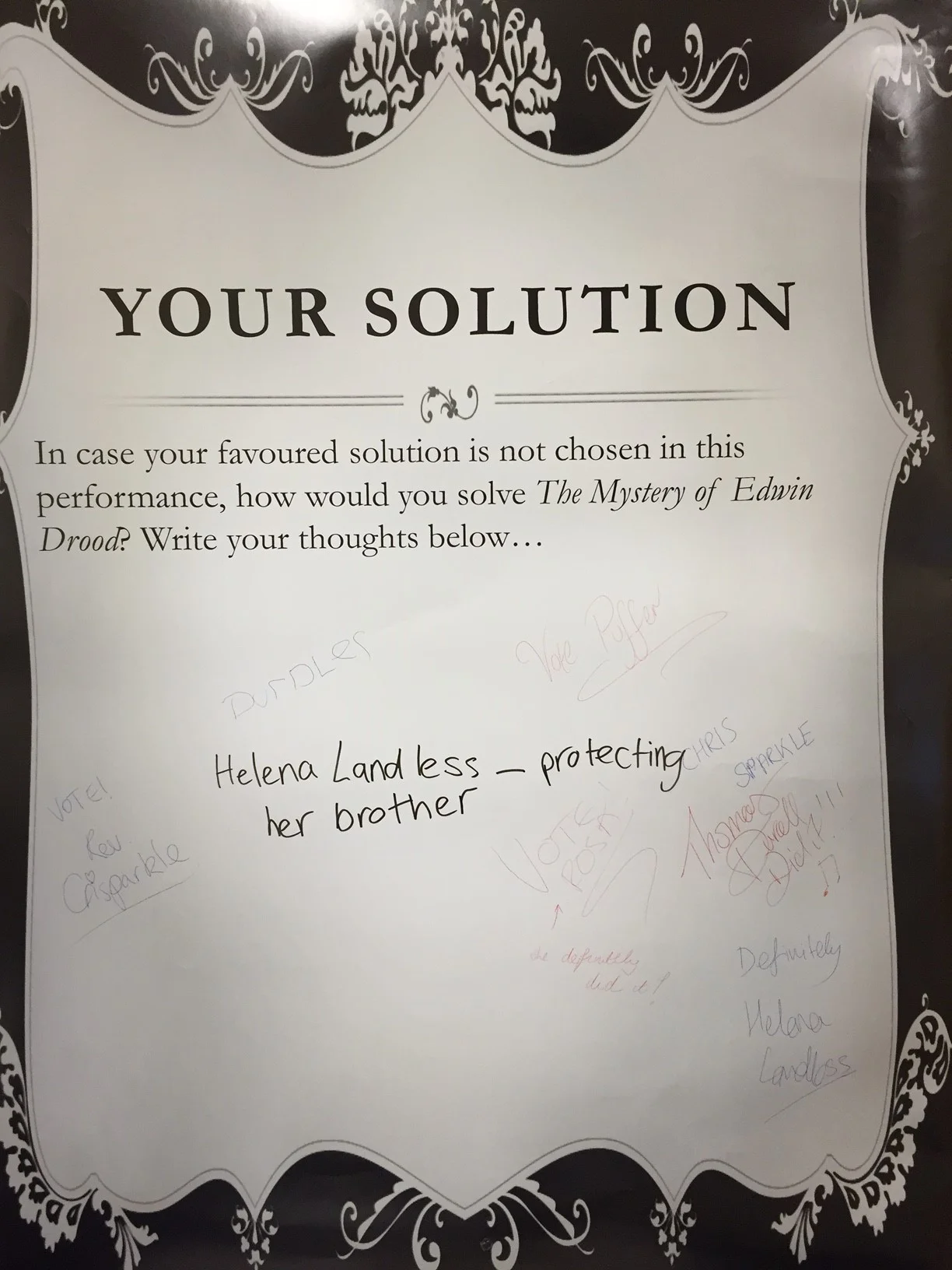

The researchers provided an exhibition of theories, clues, and potential endings that have intrigued literary scholars to aid the audience with their decision. Alongside this, we provided audience members with the space to add their own opinions.

The results for the five show run were as follows:

Wednesday

Detective Neville Landless

Murderer Bazzard

Lovers Durdles and Rosa Bud

Thursday

Detective Bazzard

Murderer Rosa Bud

Lovers Helena and Neville Landless

Friday

Detective Bazzard

Murderer Neville Landless

Lovers Princess Puffer and Rev Crisparkle

Saturday matinee

Detective Bazzard

Murderer Rosa Bud

Lovers Princess Puffer and Deputy

Saturday Evening

Detective Helena Landless

Murderer Rosa Bud

Lovers Princess Puffer and Bazzard

The audiences in Glasgow thought that Rosa Bud, as the innocent, girlish fiancée of Edwin Drood was the most likely candidate for the murderer and the mysterious opium madam, the Princess Puffer, needed a happy ending. In rehearsals, including the invited dress rehearsal, and on the Thursday night, the most common combination for the lovers was the incestuous one. These solutions, particularly the latter, are perhaps not the most Dickensian, but the musical does highlight the most plausible suggestions from literary scholarship. For example, the musical is quick to point out that Dickens makes much of the introduction of Bazzard, a clerk to Rev. Crisparkle, yet he is subsequently always ‘away on business’ when alluded to. This prompted the musical adaptation to have Bazzard seek solace in the fact that Dickens could have intended a greater purpose for the minor character. It is this hope that inspires Bazzard’s solo ‘Never the Luck’ in which the Victorian actor playing Bazzard fantasises about being called upon to play the lead one day.

While we recognised that the audience vote was to an extent influenced by friendships with cast members or a preference for a comic solution, the production and its exhibition saw that the audience could consider the multitude of possible solutions regardless of what won the audience vote. In fact, we had several instances where audience members had enjoyed the show but were unhappy with the ending they had seen, so returned two and three times to vote for a different ending. Not a bad result for engaging the public with a nineteenth-century unfinished novel.