Writing Academic Articles

One of the reasons that I applied for the PGR Blog internship is that I have always received good feedback on my writing and I wanted to gain some experience of using a non-academic style. This kind of writing is fun and it’s nice to have freedom of style, grammar, and vocabulary, but writing academically is another kettle of fish. There are subject-dependent guidelines, journal specific styles, and higher expectations all around. I’m going to try and avoid discussing any of those, though, and focus on the commonalities of good academic writing across all disciplines. Something I have a little experience with, since my supervisor started sending me our group’s papers to edit!

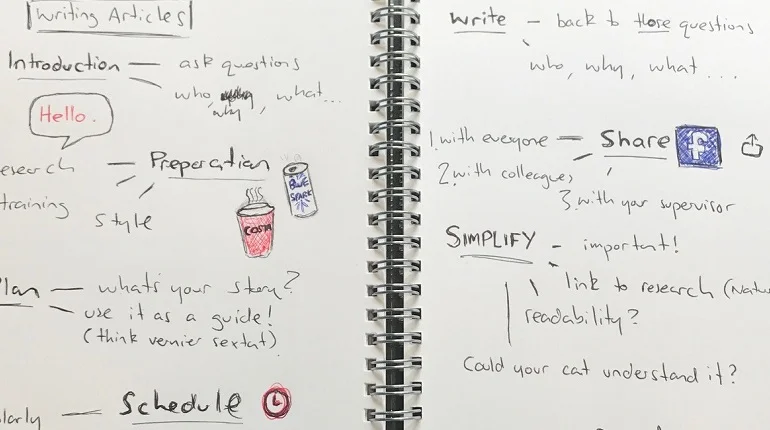

The way that I approach writing articles is usually by asking myself a series of simple questions:

Who is my audience?

Why do they care about what I’m writing?

What are my key points?

Is it easy to read?

I tend to find that if I have answers for these questions (the last one has to be a yes) then I can write quite easily. Whatever stage you are at in your academic writing, there are a number of steps to go through to produce a paper.

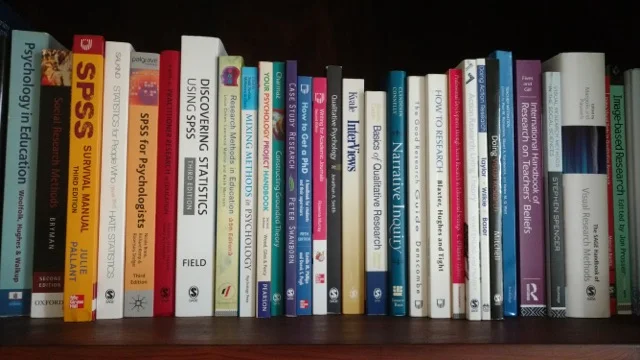

Preparation

Preparation comes in different forms. While it’s pretty obvious that you can’t write a paper without first carrying out the research, it might be less clear if you need to brush up on your writing technique. Having confidence in your writing is a good start, but it’s worth bearing in mind that the required tone of academic journals might be different to the one you are used to. My advice is to read as many papers from within your niche as you can, speak to your supervisor and colleagues (if you are part of a research group), and seek support if you feel it would be beneficial.

The University offers support for all levels of writing. As PGRs we are lucky enough to have a dedicated Postgraduate Research Advisor for writing. Jennifer Boyle offers one-to-one support as well as workshops and college specific courses—some of those specifically related to writing in an academic setting.

If you are looking for more information on what kinds of things are on offer from the University then Jennifer’s blog post on Developing Your Writing Skills is a good place to start. You should also check out your college specific training programmes (MVLS, Science & Engineering, Social Sciences and Arts) for courses aimed at improving your writing skills.

Plan

Every paper you produce tells a story. What story do you want to tell? If you haven’t heard of Free Writing then you should look it up. The basic idea is that you write whatever comes to mind about your subject, without worrying about spelling, grammar, punctuation, or any of the boring aspects of writing. I find it useful during the early stages, as a way of finding out what story I’m trying to tell. When I talk about a plan, I don’t mean a rigid, unchangeable set of instructions. Look back at your Free Writing and select the ideas and concepts you want to flesh out. I use bullet points, boxes and arrows to work out roughly what I want to say. I use it as a guide to move forward. It’s important to know that not everything on my plan makes it into the final draft and there are always parts of the final draft that weren’t in the plan.

Schedule

Schedule your writing into your working routine. Whether it’s one to two hours each day, or an entire day per week, making time for your writing is important. Us academics have a tendency to let writing become secondary to our research—something that gets in the way of the science—but writing is just as important as the science. As I said in my previous post: what use is changing the world if you don’t bother telling anyone about it?

Write

Once you have an idea of what you want to say, and have set aside the time to say it, write. Start fleshing your ideas out into an article. Keep in mind those questions from before: who are your audience? Why do they care about what you are writing? And what are your key points? These questions will dictate the register you use.

Share

If your article is aimed at a journal then it is likely going to be peer reviewed. Why not get ahead of the game and have someone you know look over it beforehand? Your friends, colleagues, wife and cat will pick up on things that you’ve missed. In the West of Scotland, we have a tendency to take criticism personal. Don’t do that. Accepting that your work isn’t perfect, and that there might be a better way of doing things, is the only way that you will improve.

Once your article has done the rounds on Facebook, ask someone with a more professional eye to look over it. I would be surprised if your supervisor didn’t want to look at it before it goes out, but if you ask a more senior PhD student or researcher you can streamline the process and shorten the literary tennis match that’s about to commence.

Simplify

This is related to the last of the questions I posed at the start of this post: is your article easy to read? Research shows that scientific papers are actually harder to read than they were a century ago. There are ways of checking your readability but be careful about putting too much emphasis on algorithms. I’m a firm believer in the ethos that if you can simplify it, you should. I might write convoluted blog posts, but I try to simplify my academic writing as much as I can.

This approach might not work for everyone and, although my aim was to cover some cross-discipline commonalities, I only have experience of writing academically within physics. Let me know if you found this piece useful, especially if you’re from a different field. Please share your ideas, techniques and resources in the comments below, or on the UofG_PGRBlog Twitter page. As Leonard Nimoy once said, ‘the more we share, the more we have.’